There's a saying that those who don't study history are doomed to repeat it. There's also a saying that those who do study history are doomed to watch others repeat it. Being a history major at a university that is very politically-focused, this is frequently made blatantly clear to me. My politically-minded classmates wander about arguing foreign and domestic policy, spatting about how we should deal with Syria, or Egypt, or whatever crisis is in the news that day. My historically-minded classmates and I wander about going, "But isn't it like when...?" But it doesn't matter. No matter how similar a situation is to the past, there will always be differences, and those differences will always stall action. So, when dive into this book, let's keep a few things in mind, shall we?

There's a saying that those who don't study history are doomed to repeat it. There's also a saying that those who do study history are doomed to watch others repeat it. Being a history major at a university that is very politically-focused, this is frequently made blatantly clear to me. My politically-minded classmates wander about arguing foreign and domestic policy, spatting about how we should deal with Syria, or Egypt, or whatever crisis is in the news that day. My historically-minded classmates and I wander about going, "But isn't it like when...?" But it doesn't matter. No matter how similar a situation is to the past, there will always be differences, and those differences will always stall action. So, when dive into this book, let's keep a few things in mind, shall we?-Iris Chang was not, by trade, a historian. She was a journalist. This means a few things. Journalists, by nature of their work, can be very, very skilled at research, finding stories, and putting them together. They're typically not so great at contextualizing those stories. I'll talk more about this later.

-Chang was also the Chinese-American daughter of two Chinese immigrants who fled China during WWII with their families.

-Guilt is a slippery animal, and can't always be placed where we would like it.

-History is never one-sided, and in modern times, it is not written exclusively by the victors.

That all said, some people will not like what I have to say here, but I still feel a responsibility to say it in the interests of being as neutral as possible.

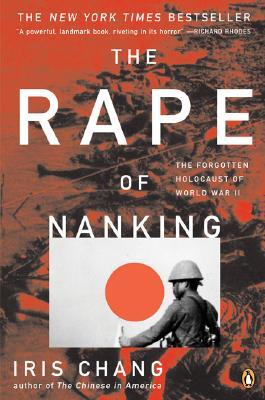

Okay, so, this is a good book for people who are not familiar with the Rape of Nanking and its place in WWII, but want to learn about it. It's a narrative history, but not a terribly scholarly one; while there are notes included at the end of the book, there are no footnotes or endnote numbers directing you to those notes, and there's no way of knowing whether or not you'll be able to track down a reference for the piece of information that interested you. This probably comes from Chang's journalistic, rather than historic, background. That's not a bad thing. "Popular history" books are all the rage these days, and I don't see anything wrong with that; they get people interested in history. We just have to keep in mind that they're not as scholarly as some other books, and consequently don't usually analyze events as closely as they could. For those wanting a quick overview of an event, this is fine. For those hoping for a complete understanding, however, it can be problematic. Chang's book is immensely readable, and I went through it in about two days. It gives a quick history of what Chang apparently sees as the Japanese culture that led to the Rape, and then covers the lead-up to the Rape, the Rape itself, and the aftermath, as well as telling what foreign individuals did and what the rest of the world knew about the events as they were happening. It's a good overview. In the epilogue, though, it gets a bit preachy. Chang talks about how Japan needs to sever ties with its past, acknowledge that the Rape was wrong, and embrace a new future. She talks about that a lot. And while she's not wrong, necessarily, she leaves out a lot of considerations.

First, as I mentioned above, we need to consider Chang's background. She's Chinese-American and was raised in the Midwest of the USA, in the midst of an extremely individualistic culture. Eastern cultures, such as China, Japan, and India, tend to be much more collectivistic than western ones. That's not bad; it's just different. It means their values are placed on the good of of the many, instead of the good of the few. It's apparently worked for them for thousands of years, so I don't see a need to judge that. What I do think we need to consider, though, is how something like the Rape of Nanking might be viewed in different cultures. I'm not Japanese; I've never been to Japan. I certainly can't speak for them. However, as someone with a background in history, I have to say that when the Japanese say they saw what they did as necessary...well, they might not be lying, like Chang claims they are. In hindsight, it's easy to see how horribly awry Japan's plans went. But in the heat of the moment, it's also very easy to see how the Japanese army, massively outnumbered in most cases in Nanking, could have seen the situation as "them or us," and chosen, as most of us would, "us." Chang mentions on repeated occasions that the Nanking natives, even unarmed, could have easily overwhelmed the Japanese through sheer numbers alone. As horrible as the Japanese actions in Nanking were, and as reprehensible as they are from an outside perspective over half a century later, it's easy to see where, at the time, those actions might have seemed necessary for self-preservation. (And let me clarify--I'm talking mostly about the killing, here. The rampant raping and torture can't really be excused, but Chang does offer a pretty good psychological analysis for why this might have happened in the epilogue, so I'll let that speak for itself.)

Second, lets consider the aspect of guilt. Who is guilty for the Rape of Nanking? There are some easy to answers to that, and some not-so-easy ones. It's hard to tell who knew what, who ordered what, who did what, especially when many documents have been destroyed and many victims refuse to speak. There is definitely guilt to be laid out, those most of the people deserving of it are probably, by this point in time, dead. Then there is the idea of collective guilt: that the youth of today's Japan are somehow responsible for the Rape of Nanking because they deny its reality and refuse to make reparations to the victims. There's a whopping problem with this analysis, and that's that you can't hold Japan's youth responsible for denying the existence of something they don't know about. I'm not sure how much has changed since Chang's book came out--it was published in 1997--but in the epilogue she talks at length about how the events of the Rape of Nanking have been censored from school curriculum, deleted from books, and shunned in the public sphere. How are you supposed to correct something you don't know about? Some people claim to have seen Bigfoot and to have evidence of his existence, but that doesn't mean I believe them. While the Rape of Nanking isn't Bigfoot, and we know that objectively, it might be hard to comprehend in an environment where it has been treated as Bigfoot for decades.

My other main problem with this is that, well, Chang is American. We Americans find it very easy to cast judgment against other peoples and refuse to do the same to ourselves. Chang criticizes Japan for enshrining some of the people who are responsible for the Rape of Nanking and practically worshipping them. I'm not going to get into the worshipping thing; that's a culture issue. But the enshrinement of war criminals I'm not afraid to tackle. Chang criticizes the emperor of Japan for knowing about the Rape and doing nothing about it--perhaps even approving of it. Fine. But if we're going to go down that path, we have to keep in mind that that's not just a Japanese trait. In Washington DC, the Vietnam memorial contains the names of soldiers known to have committed atrocities in Asia, such as cutting off the ears of victims for trophies. The Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb, is preserved as a national treasure at the National Air and Space Museum's annex. We condemn Iranians for flooding to the street chanting against the USA, but when Osama bin Laden was killed, thousands flooded the National Mall, White House, and 9/11 Memorial Site chanting "USA, USA" in a way that is unnervingly similar--we were, after all, celebrating someone's death. I am not saying that enshrining war criminals is worthy of praise. But I am saying that those in glass houses shouldn't throw stones, and if you're going to write about history, even an isolated event such as the Rape of Nanking, you still have to consider its place--and your conclusions--in a larger context.

Chang's book is a good introduction to the Rape of Nanking, but it is weak in the historiographical elements and modern context that are vital to actually understanding historical events in their entirety. I enjoyed reading it, but I am a bit worried about the message that it could leave someone who read only this book and considered it the "all you need to know about the Rape of Nanking" book. That message seems to be that the Chinese are all that is good, the Japanese are all that is bad, and the current generation needs to pay for the sins of their forefathers in order to move forward to a better world. But if we're hoping to move forward to a better world, wouldn't holding grudges not be the way to go? Honestly, the Japanese government as a whole probably should make some sort of apology or reparation to remaining survivors or the families of victims of the Rape of Nanking--but I don't think we should make the leap that this would magically solve the problem, and to some degree that seems to be what Chang implies.

3 stars out of 5.

No comments:

Post a Comment